Astrophotos

Night Sights from Stony Ridge Observatory

A Legacy in Photographs

Members of SRO and visiting astronomers alike have been actively recording the sky for the entirety of the observatory’s existence. Links on this page point to a small but representative array of imagery spanning the period.

Primarily featuring the 30-inch reflector, the results document the evolution of equipment and methods in use at the Observatory and whet the appetite for opportunities to come.

The advent of sophisticated electronic cameras and the enthusiastic, steady dedication of SRO’s members to keep pace with the demands of caretaking and modernizing the venerable Carroll telescope ensures that this activity will not only continue, but expand.

Ryan Kinnett

There are challenges to be sure: the encroachment of light pollution, the proliferation of photo-smearing satellites, and the responsibilities of facility maintenance are but a few. And yet, the opportunity to photograph the heavens from SRO, in the midst of whispering pines and the solitude of the night, is a call that beckons today just as it did in the 1950s.

Check back often – new content will be posted from both the archives and current efforts on a timely basis.

The Horsehead Nebula - IC434

This photo of the well-named nebula, located near the belt of Orion, was made with the 30-inch (.76m) telescope on October 6, 1973. In their 45 minute exposure, observers Ken Owensby and Bill Benton from the astronomy department at USC used Kodak's 103 A-0 spectral sensitivity film, a favorite choice of astronomers at the time.

Many of the brightest objects in the heavens bear "M" numbers, for example, M45, for the Pleaides in neighboring Taurus. The "M" denotes French astronomer Charles Messier who compiled a list of stationary objects to compare against the motion of suspected comets he hunted in the 1700s. The Horsehead nebula did not make the list...

Owing to the overpowering light of 2nd magnitude Alnitak, this dark nebula is difficult to spot visually. It finds a place in the so-called "Index Catalog (IC)," an addition to the original compilation by JLE Dreyer in 1888 called the "New General Catalog" from which NGC numbers are derived. Most of the IC entries came from photography which steadily revealed more of the "deep sky" than could be seen by eye alone.

The Horsehead Nebula - IC434

This photo of the well-named nebula, located near the belt of Orion, was made with the 30-inch (.76m) telescope on October 6, 1973. In their 45 minute exposure, observers Ken Owensby and Bill Benton from the astronomy department at USC used Kodak's 103 A-0 spectral sensitivity film, a favorite choice of astronomers at the time.

Many of the brightest objects in the heavens bear "M" numbers, for example, M45, for the Pleaides in neighboring Taurus. The "M" denotes French astronomer Charles Messier who compiled a list of stationary objects to compare against the motion of suspected comets he hunted in the 1700s. The Horsehead nebula did not make the list...

Owing to the overpowering light of 2nd magnitude Alnitak, this dark nebula is difficult to spot visually. It finds a place in the so-called "Index Catalog (IC)," an addition to the original compilation by JLE Dreyer in 1888 called the "New General Catalog" from which NGC numbers are derived. Most of the IC entries came from photography which steadily revealed more of the "deep sky" than could be seen by eye alone.

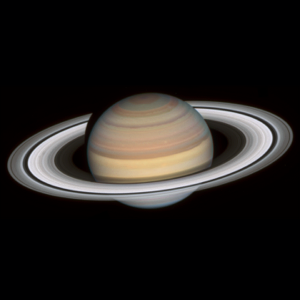

Solar System

Portraits of the Sun's Family

Many of the images in this section were recorded on single-shot film, the only practical medium at the time. (Motion picture stock was available and had been used for the Lunar Mapping Program but was impractical for most applications.)

Electronic detectors are now the instruments of choice, and were used to record the shots of the Moon and Saturn seen on the adjacent panels.

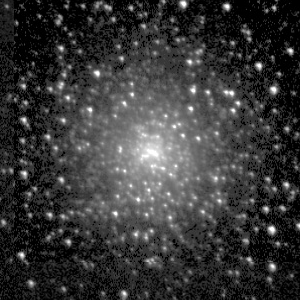

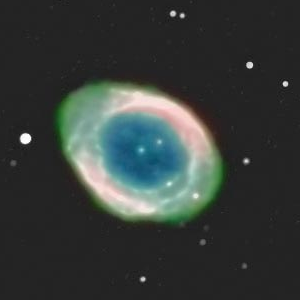

Deep Sky

Ancient Light Arrives at Stony Ridge Observatory

These objects are seen not as they are, but as they existed many years ago. How “old” is this light? In one sense – it hasn’t aged at all. Time does not have meaning for light traveling in a vacuum, for it travels at “the speed of itself!” According to the Theory of Relativity, time stops for it.

Photons originate from deep within stellar interiors as a byproduct of nuclear fusion. Once created, they begin a tortuous, collision-dominated journey until reaching high enough in the star’s thinner, less opaque atmosphere to radiate away. Astronomers estimate that the average duration of such escape maneuvering is on the order of tens of millions of years.

Once liberated, they stream away for the interstellar part of the odyssey, acting both as a wave and a particle. Having been emitted from objects within the Milky Way, the photons traveled between tens of years to hundreds of thousands to reach SRO.

The trip from the galaxies was much longer – millions of years – and yet the ones pictured on these pages are still relatively near compared to those detected from the furthest reaches of the observable realm.

How far is that??

Over 13 billion light years away – a calculable but wholly unfathomable distance!