Founder Focus

George A. Carroll

Aviation Pioneer,

Engineer,

Telescope Maker,

The Guiding Force

George A. Carroll

"As Hale was to Palomar..."

Aviation Pioneer,

Engineer,

Telescope Maker,

The Guiding Force

George A. Carroll

"As Hale was to Palomar..."

From Lone Star to Starstruck...

Experiences in the Skies Above Texas Foreshadow Lifelong Passions

James Albert Jackson Carroll was born on April 4, 1902, in Belton, Texas, a small town near Temple and about midway between Austin and Waco.

He grew up on a farm in the nearby Tennessee Valley, an area between Belton and Killeen (to the west), so named for settlers who migrated there from the Volunteer state years before. In 1910, at the age of eight, his interest in astronomy was sparked by the apparition of Halley’s Comet, this coming on the heels of an even more spectacular interloper, the Great Daylight Comet, from earlier that year.

When just a lad of 16 in Killeen, “George” (his adopted name of unknown origin) built and flew his first airplane. At that time, he was one of the youngest pilots in the country, and his connection with aviation would be both significant and long lasting. The 1920s saw Carroll “barnstorming” through Lone Star counties, flying stunts for circus crowds, this in addition to other thrill-based spectacles such as racing motorcycles and operating speedboats at carnivals.

"Halley's Comet," 1910 Apparition

The appearance of comet Halley would help ignite a devotion that would burn for the rest of Carroll's life. It was not the brightest comet that year; that distinction belonging to "The Great Daylight Comet" whose discovery is uncredited and about which George did not recount when recalling his younger years.

The majesty and memory of inky black skies over the Texas Hill Country, loaded with stars that seemed "close enough to touch," would also serve as a potent kindling influence.

Halley's Comet, 1910 Apparition

The appearance of comet Halley would help ignite a devotion that would burn for the rest of Carroll's life. It was not the brightest comet that year; that distinction belonging to "The Great Daylight Comet" whose discovery is uncredited and about which George did not recount when recalling his younger years.

The majesty and memory of inky black skies over the Texas Hill Country, loaded with stars that seemed "close enough to touch," would also serve as a potent kindling influence.

Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

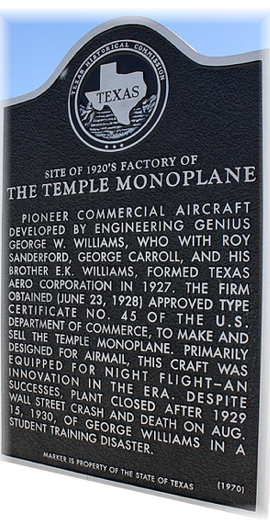

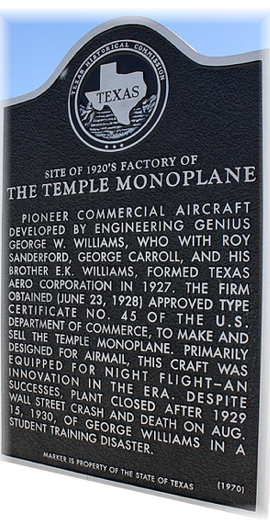

In 1927, he joined with a trio of other partners to form the Texas Aero Corporation, the first commercial aircraft fabricating facility in the state. Along with George Williams, Carroll designed and built the “Temple Monoplane,” a craft intended to expedite the delivery of newspapers and mail to the state’s remote counties.

Temple "Sportsman" Monoplane

Carroll was just 25 years old when he joined with three other partners to manufacture aeroplanes like the one pictured above. He had already been a pilot for nine years, honing both his stick and rudder skills as well as his understanding of applied aerodynamics while stunt flying throughout Texas. These experiences were of considerable value to the group's fledgling engineering enterprise.

This model is flyable but is not "as manufactured," though its parts are all genuine. They were hunted down and assembled by a restorer who "mined" them from spares and cast offs found at facilities once used by Texas Aero. The plane is on exhibit at the Frontiers of Flight Museum at Love Field in Dallas. It is believed that no original Temple Monoplanes are still in existence.

Temple "Sportsman" Monoplane

Carroll was just 25 years old when he joined with three other partners to manufacture aeroplanes like the one pictured above. He had already been a pilot for nine years, honing both his stick and rudder skills as well as his understanding of applied aerodynamics while stunt flying throughout Texas. These experiences were of considerable value to the group's fledgling engineering enterprise.

This model is flyable but is not "as manufactured," though its parts are all genuine. They were hunted down and assembled by a restorer who "mined" them from spares and cast offs found at facilities once used by Texas Aero. The plane is on exhibit at the Frontiers of Flight Museum at Love Field in Dallas. It is believed that no original Temple Monoplanes are still in existence.

RuthAS, CC BY 3.0,

via Wikimedia Commons

In 1970, the State of Texas erected a memorial plaque at the site of Texas Aero Corporation’s first hangar – demolished long before – recognizing Carroll and the other founders for their innovations in a relatively new and rapidly growing industry.

Nicolas Henderson,

via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0 DEED

Cropped by Stony Ridge Observatory, Inc.

The fortunes of the company were short lived, sunk by two tragic crashes: one on Wall Street in 1929 and the other in an airplane involving George Williams the following year. In a bit of dark irony, the Temple Daily Telegram reported that the original historical marker met with similar misfortune, having been stolen sometime between 2004 and 2007. It was replaced by the one pictured above in 2010 at a dedication ceremony which included both family members of the aviation pioneers and the public.

After 1930, Carroll moved to Louisiana, there flying a seaplane used to resupply offshore drilling rigs for the Texas Oil Company. Later, he relocated to Ft. Worth to take a position as a Maintenance Engineer for the recently formed Braniff Airways, this at Love Field in Dallas.

A Telescope Maker is Born on the Way Westward

In 1934, Carroll made his first astronomical telescope, an exercise that was becoming popular at the time.

It’s easy to imagine a growing interest in this pursuit, for even before the space age of the late 50s and early 60s, “big astronomy” and the promise of the 200-inch Palomar telescope was creating a lot of buzz. It helped to spur a surge in hobby astronomy that resulted in the birth of supportive companies and periodicals like The Sky and The Telescope. The path of those magazines as merged into Sky & Telescope would intersect at various times with Carroll’s for several decades.

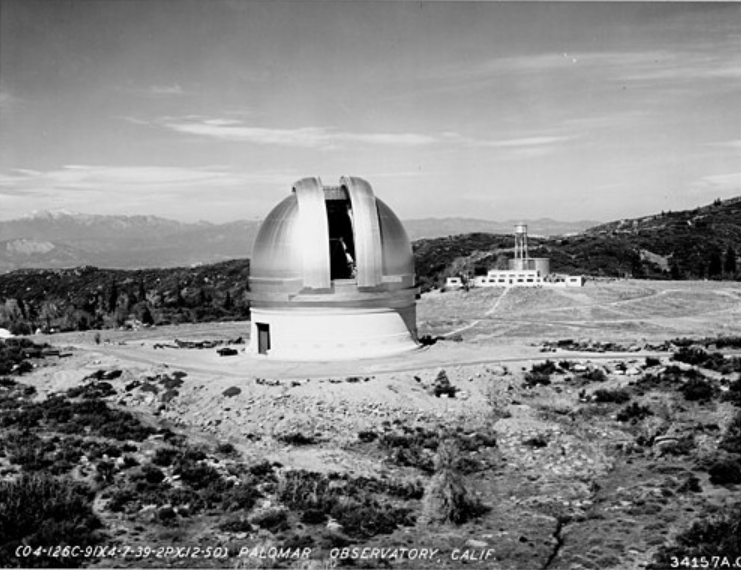

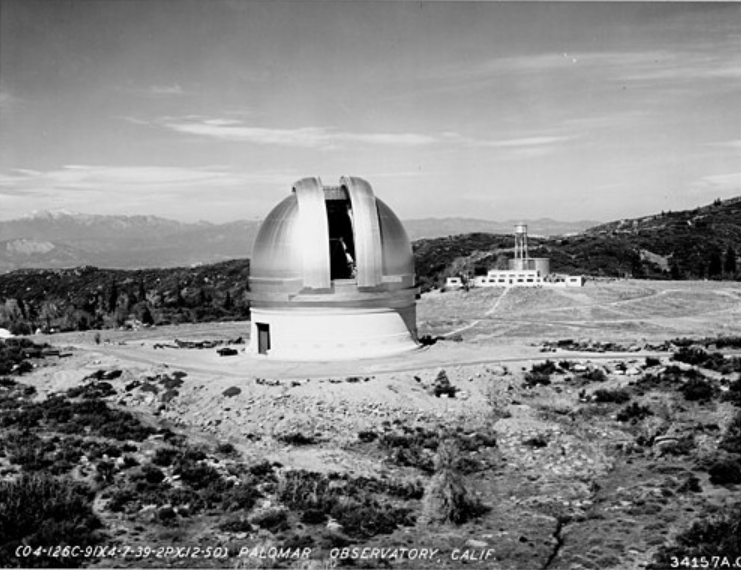

Palomar Observatory, 1939,

Around the time of George Carroll’s arrival in California

and Nine Years Before “First Light”

National Archives and Records Administration, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

In 1940, a westward career migration ensued, this to California and a job offer at the Vega Aircraft Corporation in Burbank. His role there, as Staff Engineer-Head of Service Design, was to troubleshoot aircraft problems at the company’s San Fernando Valley plant and additionally, several locations around the country as required by the Army Air Force, a principal customer during WWII.

Eventually, Vega Aircraft became absorbed by Lockheed, where George continued on as a Design-Development Engineer.

Lockheed Life

Secrets, Sales, and the Sun

In 1943, Lockheed formed a division called the Advanced Development Projects (ADP) Unit at their expanding facilities in Burbank. The ADP produced classified, cutting-edge experimental products for aviation, the military, and later, for space research. It eventually acquired the title of the “Skunk Works,” where all kinds of strange, smelly concoctions were created.

For Lockheed employees at the facility, it wasn’t abstract: funky odors actually did waft through the facility, this from a nearby plastics manufacturer! (The Skunk moniker is a derivative of a fictitious wooded place – “Skonk Works” – mentioned in Li’l Abner, a popular comic strip of the day. It was there that nasty ingredients were brewed into stinky potions and Lockheed workers couldn’t resist adopting the Skonk Works name for the odiferous similarities they endured. Objections by attorneys for the cartoonist forced Skonk to be abandoned.)

George had ties to the Skunk Works from its inception through the early 1960’s. It was during this time, beginning in 1947, that his association with the future Stony Ridge Observatory effort began to develop. Though friends and acquaintances from that era were generally aware of Carroll’s affiliation with the the ADP and its spooky overtones, none could be certain of his role there. He was perfectly comfortable keeping certain things to himself and was not the type to brag.

George Won't Tell...

Black planes, black programs, information blackout. Carroll didn't talk about his work at Lockheed because it was highly classified. And then, of course, there was "Rule 13" to think about...

This emblem, high on the tail of an SR-71, was the moniker for the famous "Skunk Works," the division responsible for developing planes like the Blackbird pictured above and, later, stealth aircraft.

George Carroll spent the better part of 20 years involved with the hush-hush there, just going about his business while keeping his eyes open and mouth shut!

George Won't Tell...

Black planes, black programs, information blackout. Carroll didn't talk about his work at Lockheed because it was highly classified. And then, of course, there was "Rule 13" to think about...

This emblem, high on the tail of an SR-71, was the moniker for the famous "Skunk Works," the division responsible for developing planes like the Blackbird pictured above and, later, stealth aircraft.

George Carroll spent the better part of 20 years involved with the hush-hush there, just going about his business while keeping his eyes open and mouth shut!

Jonathan Cutrer from San Angelo, Texas, United States,

CC BY 2.0,

via Wikimedia Commons

(Changes made to original)

Neither were any of the closely knit SRO members seemingly able to pry Carroll’s lips about his work at the highly secretive research facility. Apparently, he was a dedicated disciple of “Rule 13,” one of fourteen dictates of Project Management established and perfected by Skunk Works founder, Clarence “Kelly” Johnson. The thirteenth principle dealt with standards of discipline with classified information. To wit:

“Access by outsiders to the project and its personnel must be strictly controlled by appropriate security measures.”

Kelly’s blueprint for governance was developed to meet a specific need at Lockheed but its tenets have been adopted in a variety of circles and may well have influenced the development of the Stony Ridge Observatory. As the SRO project was formulated and progressed, the group was kept small, responsibility was delegated to entrusted members whose contributions went beyond just their areas of expertise, specifications were detailed, and there was regular reporting. Each of these are bullet points embodied in Kelly’s approach.

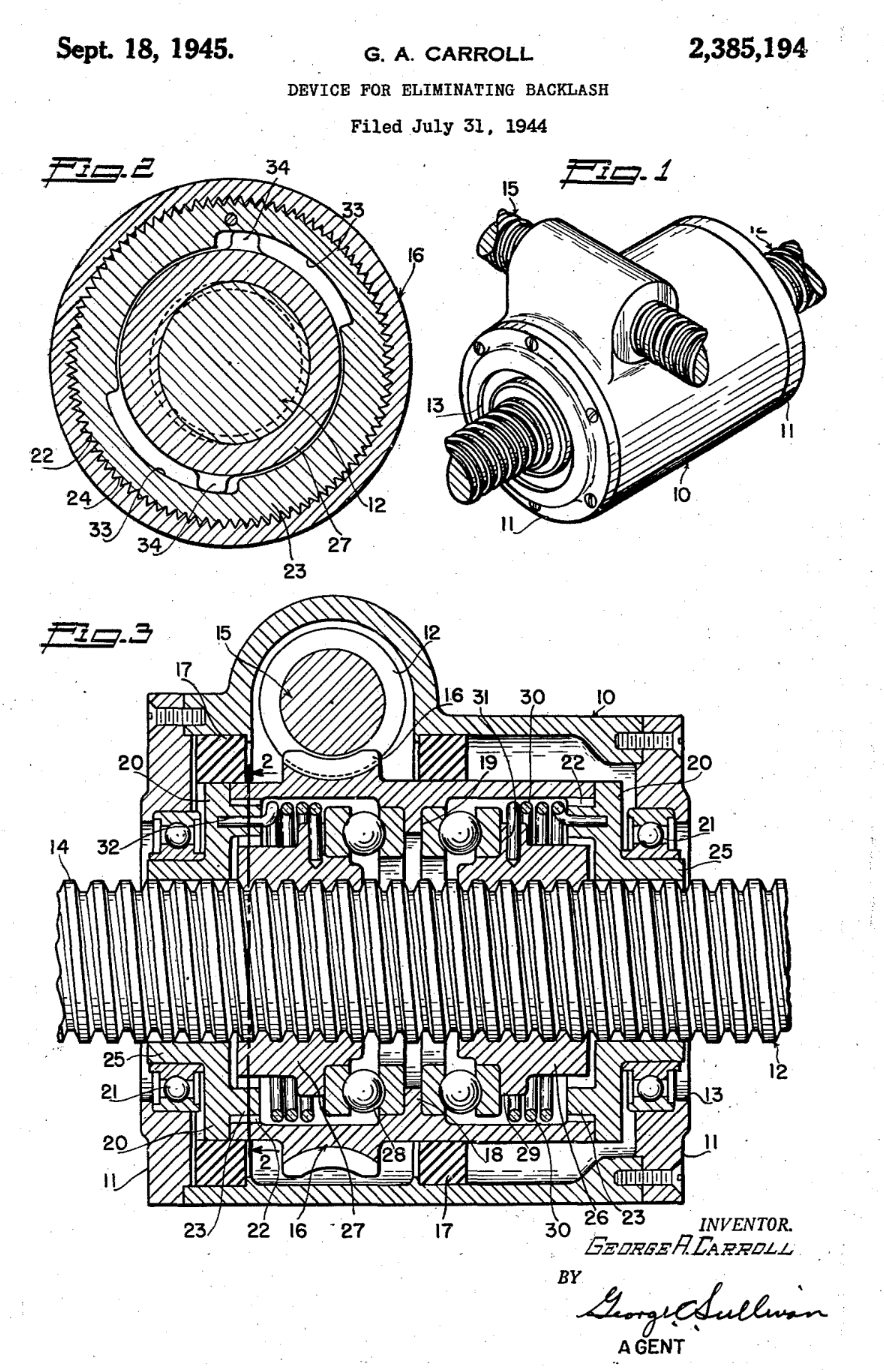

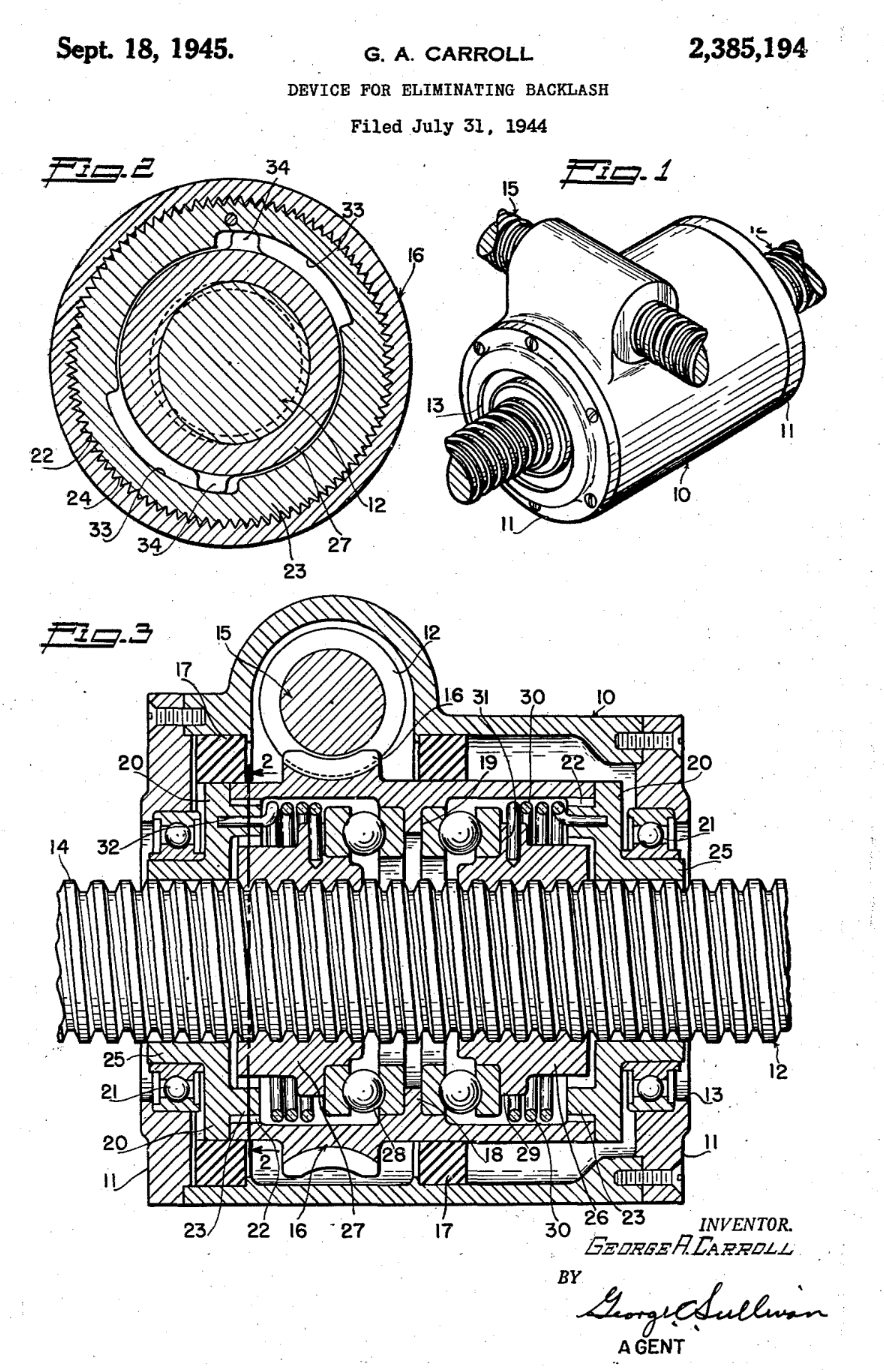

Backlash Be Gone

This engineering drawing accompanied George Carroll's proposal to eliminate backlash from worm drive systems whether the moving component was the screw or the capture nut. Ostensibly, it was submitted to solve issues with aircraft mechanical systems such as wing flap actuators, this at Lockheed and other manufacturers.

However, the "off label" application to astronomical components is obvious, particularly with regard to correctors for an equatorial mount's Declination axis. As opposed to the driving force in Right Ascension which moves only forward while tracking, Declination generally requires "back and forth" guiding control where backlash - slop in the meshing of gears when reversing direction - can be highly problematic.

Whether Carroll had this in mind as an adjunct isn't known with certainty, but it seems quite plausible that he might try to solve a nighttime problem with his day job.

In addition to the drawing above, a fully detailed working explanation of all parts was included in Carroll's initiative. The patent was awarded in the Fall of 1945, just after the end of WWII.

Backlash Be Gone

This engineering drawing accompanied George Carroll's proposal to eliminate backlash from worm drive systems whether the moving component was the screw or the capture nut. Ostensibly, it was submitted to solve issues with aircraft mechanical systems such as wing flap actuators, this at Lockheed and other manufacturers.

However, the "off label" application to astronomical components is obvious, particularly with regard to correctors for an equatorial mount's Declination axis. As opposed to the driving force in Right Ascension which moves only forward while tracking, Declination generally requires "back and forth" guiding control where backlash - slop in the meshing of gears when reversing direction - can be highly problematic.

Whether Carroll had this in mind as an adjunct isn't known with certainty, but it seems quite plausible that he might try to solve a nighttime problem with his day job.

In addition to the drawing above, a fully detailed working explanation of all parts was included in Carroll's initiative. The patent was awarded in the Fall of 1945, just after the end of WWII.

Carroll’s aviation career, which took him from modest, dusty roots “deep in the heart of Texas” to the squeaky-clean environs of a top secret factory awash in black budget money, was both varied and hands-on. According to the eventual eulogy delivered by his son, George Jr., Carroll still found time to build 20 aircraft, including a gyro copter. But the end of that career simply gave him more time to sink his teeth into the next big thing: astronomical instrumentation.

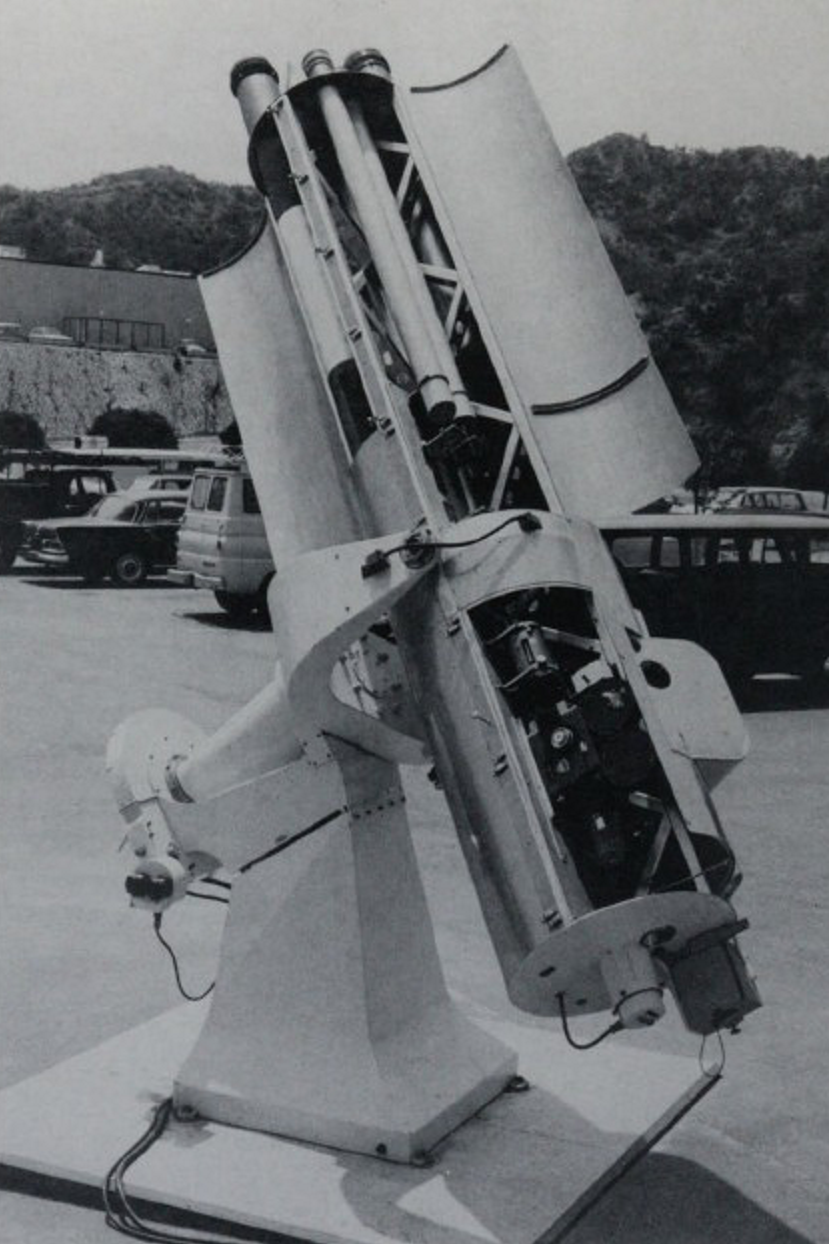

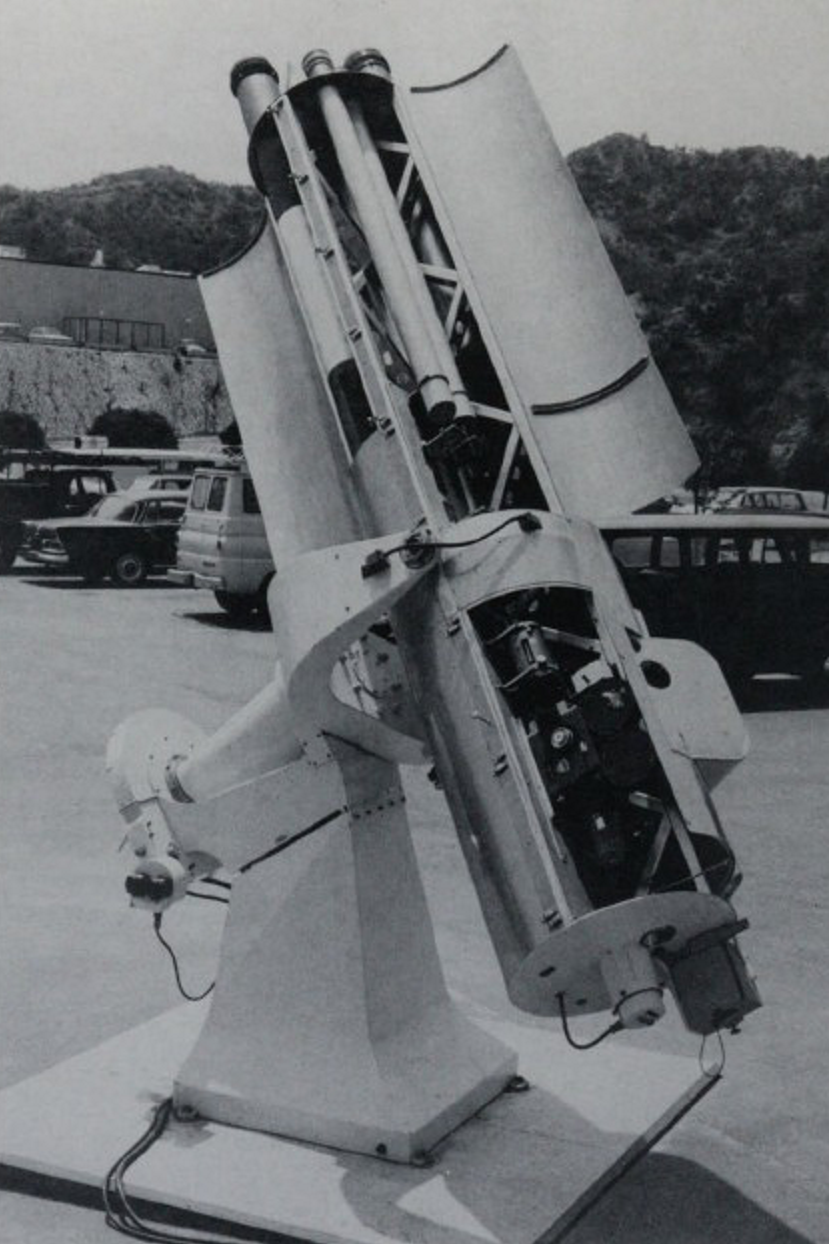

Lockheed Spar Telescope

This telescope was designed by George Carroll while serving on the staff of Lockheed's Briar Summit Solar Observatory. It is one of many such telescopes he designed which employed "spar" construction.

Spar telescopes are so-named for the unique support structure upon which several instruments may be mounted, all being capable of observing the sun simultaneously.

Four ribs, each consisting of a sawtooth series of triangular braces, are mounted at cardinal points within the substructure. Bulkheads at either end of the "tube" ensure rigidity.

Note the mounting and drive system. They feature Carroll's design preferences, sharing many of the trademark construction details he used in previous telescopes, including the 30-inch at Stony Ridge.

Lockheed Spar Telescope

This telescope was designed by George Carroll while serving on the staff of Lockheed's Briar Summit Solar Observatory. It is one of many such telescopes he designed which employed "spar" construction.

Spar telescopes are so-named for the unique support structure upon which several instruments may be mounted, all being capable of observing the sun simultaneously.

Four ribs, each consisting of a sawtooth series of triangular braces, are mounted at cardinal points within the substructure. Bulkheads at either end of the "tube" ensure rigidity.

Note the mounting and drive system. They feature Carroll's design preferences, sharing many of the trademark construction details he used in previous telescopes, including the 30-inch at Stony Ridge.

Sky and Telescope, July, 1970

The Stony Ridge Years

Hightlights of a History

1947

Carroll and 2 others, Jerome B. White and Ernest R. Siefkin, form the “Association of Amateur Astronomers.”

1957

The Association of Amateur Astronomers, then numbering 15 members, file papers to change the name of the organization to Stony Ridge Observatory, Inc (SRO). Construction begins immediately to build an observatory housing a large reflecting telescope for the benefit of amateur astronomers. George Carroll leads the design and engineering for this facility.

1963

Stony Ridge Observatory is completed with financial assistance from Lockheed, itself under contract to provide support to the USAF program which prepared the Lunar Aeronautical Chart (LAC) series. There exists a timely need for observatories capable of taking high-resolution images of the lunar surface to aid the feasibility and site selection studies for the Apollo program. Lockheed furnishes quid pro quo funds to finish SRO’s construction in exchange for 1600 hours of telescope time.

1971

George Carroll is awarded the “G. Bruce Blair Award,” by the Western Amateur Astronomers for his important contribution to amateur astronomy. This honor has often been called the “Nobel Prize” for amateur astronomers.

Ad Astra Contendere

Departure

In 1987, on July 7, George Carroll died in Tujunga, California. He was 85 years old. At the time, comet Halley had completed another perihelion encounter barely a year earlier. Thus it can be observed that the 1910 and 1986 apparitions served as fitting bookends to his life in astronomy, both long and well-lived.