Lunar

Mapping

Program

A Grim Picture

c1963 - Nightmarish Times for the Stony Ridge Dream

To date, the observatory had only been partially built and 100% of that funded solely on the backs (and from the wallets) of the original 15 members of the Association of Amateur Astronomers (AAA), as SRO was known in those early years. At the many design/construction meetings held in the members’ homes, exactly how they would continue to such an undertaking was always at the top of the agenda. The family burden must have been extraordinary.

What the members could not have possibly known at the time was that help was on the way via a long, strangely winding route that originated years before in Southwest Asia then snaked its way through an obscure bay in the Caribbean, an east Florida cape, and a podium in Washington DC from which an audacious challenge had been issued by US president John F. Kennedy. On May 25, 1961 he’d implored Congress and the nation to embrace a goal in which the United States would send astronauts to the moon, land them, and bring them home before the end of the decade.

From that Capitol Hill epicenter, shock waves would reverberate through the country and one day find their way to the Angeles National Forest and Stony Ridge in a crucial and profound way. By the middle of 1963 that seismic propogation was close and when it finally manifested, the effect was pure relief.

What's "Really" Up There?

Meeting the goal to "land a man on the Moon and return him safely to earth..." required, among other things, choosing a touchdown point on a body littered with geographic obstacles: mountains, rilles, domes, scarps, and, of course, craters beyond counting. Accurate lunar cartography became a paramount concern.

Although Ranger (and later, Surveyor and Lunar Orbiter) spacecraft were dispatched to provide photographic reconnaissance of our neighbor, Earth-based observation was handy and still essential. This image, one of thousands taken at SRO in support of Project Apollo helped meet that demand and one other pressing imperative, this much nearer to the vision of the Founders: completion of the observatory itself.

Although not particularly detailed, the photo above, taken through the 30-inch Carroll telescope, shows the region around one of the six eventual landing sites. In July, 1971, Apollo 15 put down near Mount Hadley, a peak amongst the Apennine range situated between the Imbrium and Serenitatis Marae.

What's "Really" Up There?

Meeting the goal to "land a man on the Moon and return him safely to earth..." required, among other things, choosing a touchdown point on a body littered with geographic obstacles: mountains, rilles, domes, scarps, and, of course, craters beyond counting. Accurate lunar cartography became a paramount concern.

Although Ranger (and later, Surveyor and Lunar Orbiter) spacecraft were dispatched to provide photographic reconnaissance of our neighbor, Earth-based observation was handy and still essential. This image, one of thousands taken at SRO in support of Project Apollo helped meet that demand and one other pressing imperative, this much nearer to the vision of the Founders: completion of the observatory itself.

Although not particularly detailed, the photo above, taken through the 30-inch Carroll telescope, shows the region around one of the six eventual landing sites. In July, 1971, Apollo 15 put down near Mount Hadley, a peak amongst the Apennine range situated between the Imbrium and Serenitatis Marae.

Stony Ridge Observatory Wins in a "Photo Finish"

Enter Lockheed-California: from Black Program King to White Knight (Kind Of)

To support the national goal, a flurry of private contracts had to be awarded, and one such company eager to participate in both the technical pursuit and the financial windfall was Lockheed-California. It entered into an agreement with the Aeronautical Charts and Information Center (ACIC) in St. Louis, Missouri (a section run by the United States Air Force) to supply it with high-resolution images of the lunar surface. This would aid the ACIC’s production of detailed geographic and topological charts to facilitate exploration of potential landing sites for Apollo astronauts.

There was only one problem for Lockheed: where will it find a facility, suitably equipped and willing to set aside a large amount of telescope time to fulfill their obligation to the ACIC? The answer was both providential and close at hand.

At that time, three AAA/SRO members, George Carroll, Norrie Roberts and Chuck Buzzetti worked at Lockheed-California. Presumably, it was through these employee contacts that Lockheed became aware of the proximate and nearly completed Stony Ridge Observatory.

As a natural consequence of their concurrent and desperate needs, SRO and Lockheed entered into a “mutual aid pact.” Lockheed would pay to bring both power and telephone service to the observatory – no small feats given the rugged and remote location of the site. In addition, it would purchase 1600 hours of observing time on the new 30-inch telescope, this over a period of 4 years. Some of the funds would be paid upfront so that the observatory could be completed. The total infusion from Lockheed was close to $21K (over $200,000 in 2024 equivalent value).

Over the Moon

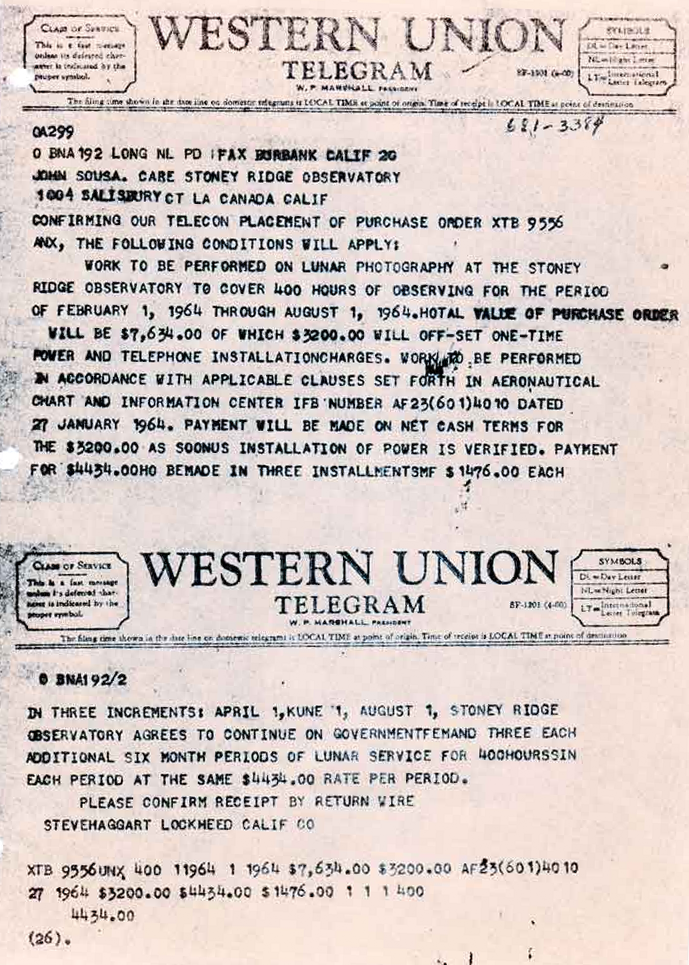

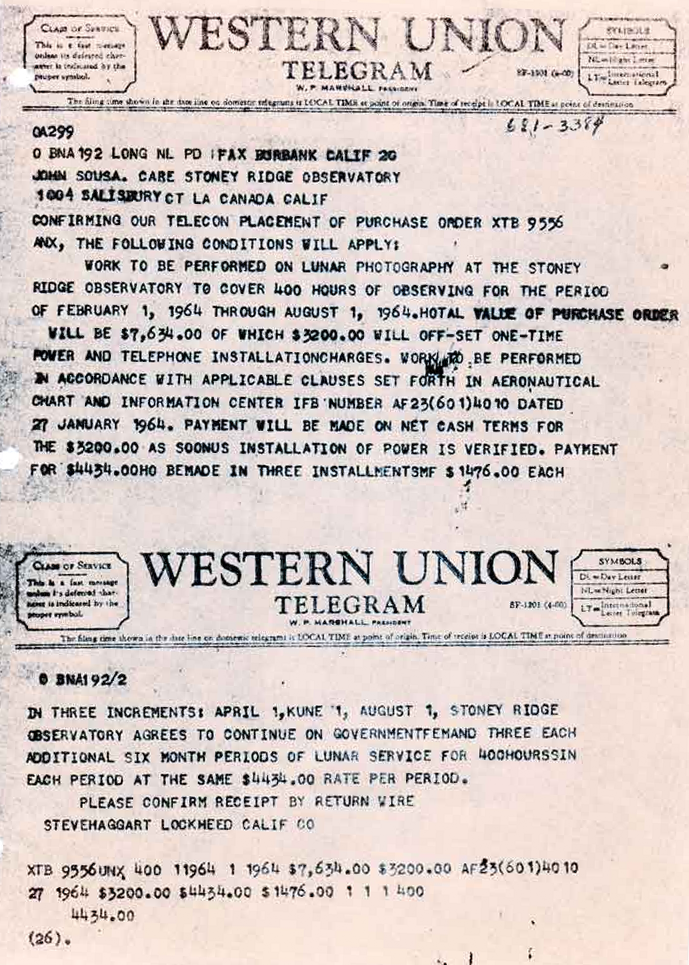

Receipt of this telegram must have been met with a mixture of both elation and relief, for the financial burdens of completing the Stony Ridge facility had become quite onerous, the subject of numerous and uncomfortable conversations amongst the Membership. It also served to validate a core mission statement of the Observatory that it serve the advancement of astronomy. Perhaps indirectly...

Beyond the obvious, who else is there to "thank" for this fortuitous circumstance? President Kennedy? How about the Soviets?!

The dots of history are often connected along circuitous paths and the SRO story is a fine example. The commitment to this observatory project began 10 months before the launch of Sputnik. The USSR, after many "firsts" in the exploration of space and the successful support of Cuban revolutionaries who repelled US-backed rebels at the Bay of Pigs did more to light Apollo's fire than any quest for pure scientific discovery. JFK, who had no particular love of space exploration simply saw the "moon program" as a way to re-establish American prestige. Thus, events far away from Charlton Flats had a large and formative effect on what would happen there, changing the fortunes of the Founders and those who came after them.

Over the Moon

Receipt of this telegram must have been met with a mixture of both elation and relief, for the financial burdens of completing the Stony Ridge facility had become quite onerous, the subject of numerous and uncomfortable conversations amongst the Membership. It also served to validate a core mission statement of the Observatory that it serve the advancement of astronomy. Perhaps indirectly...

Beyond the obvious, who else is there to "thank" for this fortuitous circumstance? President Kennedy? How about the Soviets?!

The dots of history are often connected along circuitous paths and the SRO story is a fine example. The commitment to this observatory project began 10 months before the launch of Sputnik. The USSR, after many "firsts" in the exploration of space and the successful support of Cuban revolutionaries who repelled US-backed rebels at the Bay of Pigs did more to light Apollo's fire than any quest for pure scientific discovery. JFK, who had no particular love of space exploration simply saw the "moon program" as a way to re-establish American prestige. Thus, events far away from Charlton Flats had a large and formative effect on what would happen there, changing the fortunes of the Founders and those who came after them.

SRO's Lunar Mapping Program, By the Numbers

Project Summary

The Lunar Mapping program commenced on Feb 1, 1964 and concluded Aug 1, 1967. During that 3.5 year span of which 1600 hours of observing time was allocated, over 13,400 high-resolution images were obtained. These were recorded on 35mm and 70mm motion picture stock using cameras furnished by Lockheed-California.

This camera, supplied by Lockheed California, was used to take “moonvies” in an effort to obtain high-resolution images of the lunar surface. The employment of motion picture equipment, exposing several frames per second, was intended to capture the fleeting and random moments of perfect seeing that can occur when looking through the eddy-filled column of atmosphere in front of a telescope. The device seems provisioned with a flip mirror system (left) for framing the target and, perhaps, focusing the image.

This strategy would find the perfect vehicle when high speed electronic cameras eventually came along, but that was well after the Lunar Mapping effort wrapped in the mid-60s.

This camera, supplied by Lockheed California, was used to take “moonvies” in an effort to obtain high-resolution images of the lunar surface. The employment of motion picture equipment, exposing several frames per second, was intended to capture the fleeting and random moments of perfect seeing that can occur when looking through the eddy-filled column of atmosphere in front of a telescope. The device seems provisioned with a flip mirror system (left) for framing the target and, perhaps, focusing the image.

This strategy would find the perfect vehicle when high speed electronic cameras eventually came along, but that was well after the Lunar Mapping effort wrapped in the mid-60s.

SRO members who assisted with the observations were John Sousa, Easy Sloman, Roy Ensign and Norrie Roberts. They worked alongside Lockheed Principal Investigators Larry Stoddard and Don Carson.

The credited contributions of SRO resulted in (at least) 8 high-resolution, shadowed topography, lunar surface graphics by the Aeronautical Charts and Information Center. Such acknowledgement can be seen in the Portrayal section of relevant charts, an example of which is highlighted in the picture below.

On July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil A. Armstrong and Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin landed on the Sea of Tranquility. Four days later, on July 24 and along with fellow crew member Michael Collins, they splashed down in the Pacific Ocean – safely. In so doing they completed a race that had consumed: a nation; almost every waking moment for some 400,000 engineers, scientists, and craftsmen of every description; the after-hours lives of a small, tight-knit group of Southern California Amateurs no less dedicated, no less talented, and no less resolute in pursuit of their goals.

Stony Ridge Observatory will always be proud of the role it played in helping the United States carry out the the most audacious and breathtaking adventure upon which man had ever embarked. Both entities – country and cadre – lived by the creed “we are Americans, and we can do anything…”

That, they did.

Cleomedes in Relief

Charts like this were produced from data taken by Stony Ridge and other major observatories equipped and willing to participate in the Lunar Mapping Program.

In particular, this one, LAC 44, is one of at least eight that specifically cite SRO as a contributor.

Cleomedes in Relief

Charts like this were produced from data taken by Stony Ridge and other major observatories equipped and willing to participate in the Lunar Mapping Program.

In particular, this one, LAC 44, is one of at least eight that specifically cite SRO as a contributor.

(Large file with Zooming and Panning enabled,

please be patient and allow

link to complete.)